Lecture 7

Data processing

- Last week, we collected a survey of Hogwarts house preferences, and tallied the data from a CSV file with Python.

- This week, we’ll collect some more data about your favorite TV shows and their genres.

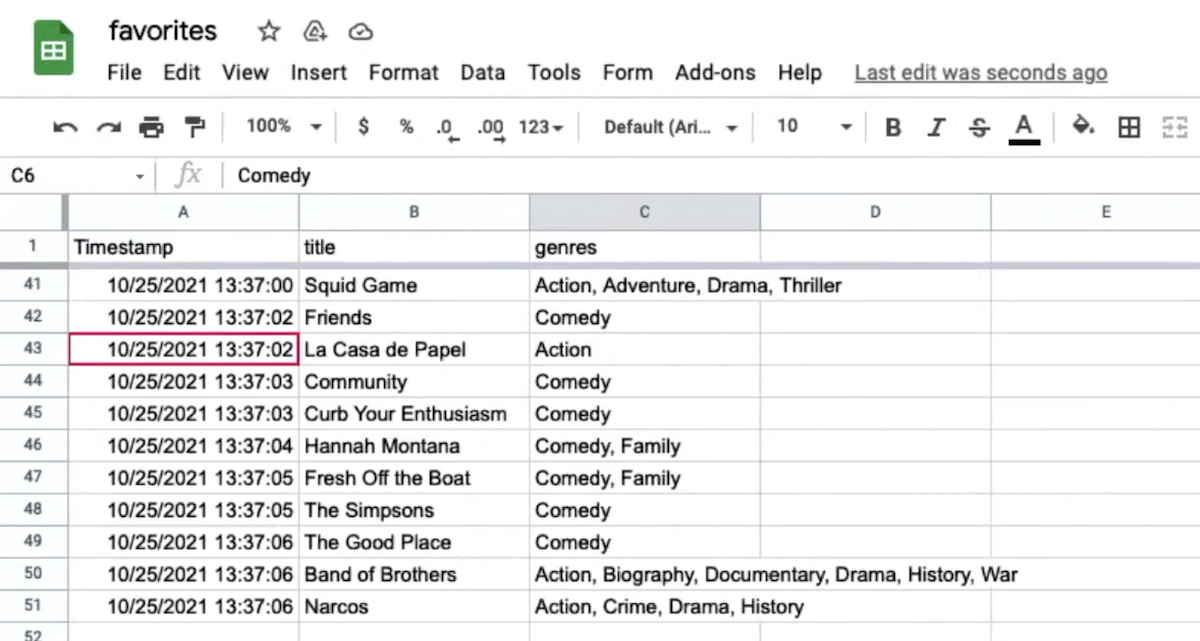

- We get hundreds of responses from the audience, and start looking at them on Google Sheets, a web-based spreadsheet application, showing our data in rows and columns:

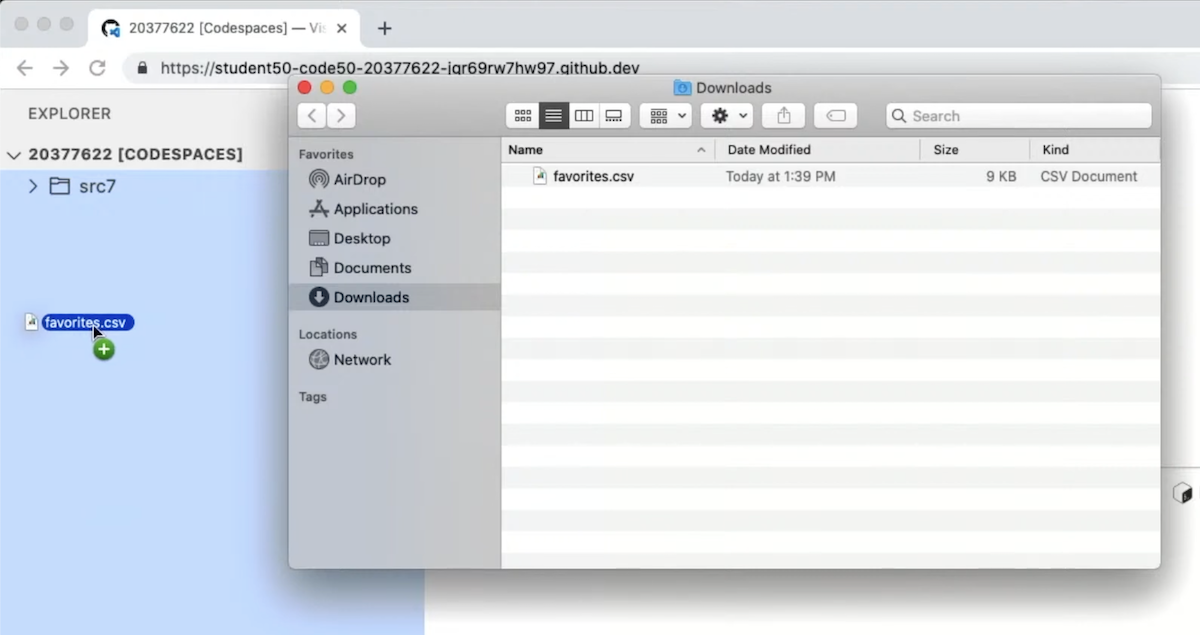

- Like we did last week, we can download our data as a CSV file, which is an example of a flat-file database, where the data for each column is separated by commas, and each row is on a new line, saved simply as a text file in ASCII or Unicode.

- A flat-file database is completely portable, which means that we can open it on nearly any operating system without special software like Microsoft Excel or Apple Numbers.

- We’ll upload the CSV file to our instance of VS Code by dragging and dropping it:

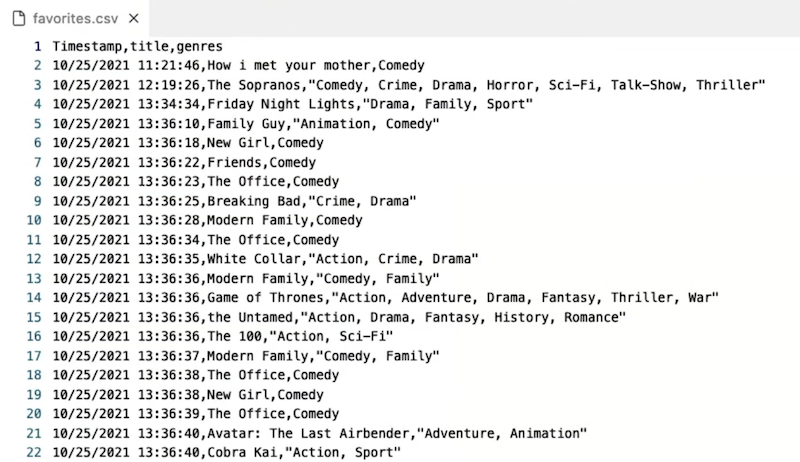

- Then, we’ll see the file opened in an editor:

- Notice that some rows have multiple genres, and those are surrounded by quotes, like

"Crime, Drama", so that the commas within our data aren’t misinterpreted.

- Notice that some rows have multiple genres, and those are surrounded by quotes, like

- Let’s write a new program,

favorites.py, to read our CSV file:import csv with open("favorites.csv", "r") as file: reader = csv.reader(file) next(reader) for row in reader: print(row[1])- We’ll open the file with a reference called

file, using thewithkeyword in Python that will close our file for us. - The

csvlibrary has areaderfunction that will create areadervariable we can use to read in the file as a CSV. - We’ll call

nextto skip the first row, since that’s the header row. - Then, we’ll use a loop to print the second column in each row, which is the title.

- We’ll open the file with a reference called

- Now, if we run our program, we’ll see a list of show titles:

$ python favorites.py ... Friends ... friends ... Friends ...- But for the show titled “Friends”, some entries are capitalized and some are lowercased.

Cleaning

- To improve our program, we’ll first use a

DictReader, dictionary reader, which creates a dictionary from each row, allowing us to access each column by its name. We also don’t need to skip the header row in this case, since theDictReaderwill use it automatically.import csv with open("favorites.csv", "r") as file: reader = csv.DictReader(file) for row in reader: print(row["title"])- Since the first row in our CSV has the names of the columns, it can be used to label each column in our data as well. Now our program will still work, even if the order of the columns are changed.

- Now let’s try to filter out duplicates in our responses:

import csv titles = [] with open("favorites.csv", "r") as file: reader = csv.DictReader(file) for row in reader: if not row["title"] in titles: titles.append(row["title"]) for title in titles: print(title)- We’ll make a new list called

titles, and only add each row’s title if it’s not already in the list. Then, we can print all the titles:$ python favorites.py ... Friends ... friends ...- We see that there are still near-duplicates, since

Friendsandfriendsare indeed different strings still.

- We see that there are still near-duplicates, since

- We’ll make a new list called

- We’ll want to change the current title to all uppercase, and remove whitespace around it, before we add it to our list:

import csv titles = [] with open("favorites.csv", "r") as file: reader = csv.DictReader(file) for row in reader: title = row["title"].strip().upper() if not title in titles: titles.append(title) for title in titles: print(title)- Now, we’ve canonicalized, or standardized, our data, and our list of titles are much cleaner:

$ python favorites.py ... NEW GIRL FRIENDS THE OFFICE BREAKING BAD ...

- Now, we’ve canonicalized, or standardized, our data, and our list of titles are much cleaner:

- It turns out that Python has another data structure built-in,

set, which ensures that all the values are unique:import csv titles = set() with open("favorites.csv", "r") as file: reader = csv.DictReader(file) for row in reader: title = row["title"].strip().upper() titles.add(title) for title in titles: print(title)- Now, we can call

addon the set, and not have to check ourselves if it’s already in the set.

- Now, we can call

- To sort the titles, we can just change our loop to

for title in sorted(titles), which will sort our set before we iterate over it:import csv titles = set() with open("favorites.csv", "r") as file: reader = csv.DictReader(file) for row in reader: title = row["title"].strip().upper() titles.add(title) for title in sorted(titles): print(title)$ python favorites.py ADVENTURE TIME ANNE WITH AN E ... AVATAR AVATAR THE LAST AIRBENDER AVATAR: THE LAST AIRBENDER ... BROOKLYN 99 BROOKLYN-99 ...- Now, we see our titles alphabetized, but there were still a few different ways that a show’s title could be entered. We’ll leave these differences there for now, since it will likely take a bit more effort to fully standardize our data.

Counting

- We can use a dictionary, instead of a set, to count the number of times we’ve seen each title, with the keys being the titles and the values being an integer counting the number of times we see each of them:

import csv titles = {} with open("favorites.csv", "r") as file: reader = csv.DictReader(file) for row in reader: title = row["title"].strip().upper() titles[title] += 1 for title in sorted(titles): print(title)- As we read each row, we increase the value stored for that title in the dictionary by 1.

- We’ll run this program, and see:

$ python favorites.py Traceback (most recent call last): File "/workspaces/20377622/favorites.py", line 9, in <module> titles[title] += 1 KeyError: 'HOW I MET YOUR MOTHER'- We have a

KeyError, since the titleHOW I MET YOUR MOTHERisn’t in the dictionary yet.

- We have a

- We’ll have to add each title to our dictionary first, and set the initial value to 1:

import csv titles = {} with open("favorites.csv", "r") as file: reader = csv.DictReader(file) for row in reader: title = row["title"].strip().upper() if title in titles: titles[title] += 1 else: titles[title] = 1 for title in sorted(titles): print(title, titles[title])- We’ll add the values, or counts, to our loop that prints every show name.

- We can also set the initial value to 0, and then increment it by 1 no matter what:

import csv titles = {} with open("favorites.csv", "r") as file: reader = csv.DictReader(file) for row in reader: title = row["title"].strip().upper() if not title in titles: titles[title] = 0 titles[title] += 1 for title in sorted(titles): print(title, titles[title])$ python favorites.py ADVENTURE TIME 1 ANNE WITH AN E 1 ARCHER 1 ... AVATAR THE LAST AIRBENDER 5 ... COMMUNITY 8 ...- Now, the key will exist in the dictionary, and we can safely refer to its value in the dictionary.

- We can sort by the values in the dictionary by changing our loop to:

... def get_value(title): return titles[title] for title in sorted(titles, key=get_value, reverse=True): print(title, titles[title])- We define a function,

f, which just returns the value of a title in the dictionary withtitles[title]. Thesortedfunction, in turn, will take in that function as the key to sort the dictionary. And we’ll also pass inreverse=Trueto sort from largest to smallest, instead of smallest to largest. - So now we’ll see the most popular shows printed:

$ python favorites.py THE OFFICE 15 FRIENDS 9 COMMUNITY 8 GAME OF THRONES 6 ...

- We define a function,

- We can actually define our function in the same line, with this syntax:

for title in sorted(titles, key=lambda title: titles[title], reverse=True): print(title, titles[title])- We can write and pass in a lambda, or anonymous function, which has no name but takes in some argument or arguments, and returns a value immediately.

- Notice that there are no parentheses or

returnkeyword, but concisely has the same effect as ourget_valuefunction earlier.

- We can also try to count all the occurrences of a specific title:

import csv counter = 0 with open("favorites.csv", "r") as file: reader = csv.DictReader(file) for row in reader: title = row["title"].strip().upper() if title == "THE OFFICE": counter += 1 print(f"Number of people who like The Office: {counter}")$ python favorites.py Number of people who like The Office: 15- We’ll have a simple

countervariable, and add one to it.

- We’ll have a simple

- Now, if our data referred to the same show in different ways, we can try to check if the word “OFFICE” was in the title at all:

import csv counter = 0 with open("favorites.csv", "r") as file: reader = csv.DictReader(file) for row in reader: title = row["title"].strip().upper() if "OFFICE" in title: counter += 1 print(f"Number of people who like The Office: {counter}")$ python favorites.py Number of people who like The Office: 16- It turns out that a row has a typo, “Thevoffice”, so now our count is correct.

- We can also use regular expressions, a standardized way to represent a pattern that a string must match.

- For example, we can write a regular expression that matches email addresses:

.*@.*\..*- The first period,

., indicates any character. The following asterisk,*, indicates 0 or more times. Then, we want an at sign,@. Then we want 0 or more characters again,.*, and then a literal period in our string, escaped with\.. Finally, we want 0 or more characters again with.*.

- The first period,

- Since we probably want at least 1 character in each segment of an email address, we should change our regular expression to:

.+@.+\..+- The plus sign,

+, means we are matching for the previous character 1 or more times. - We can restrict the domain of the email to

.eduby changing our regular expression to.+@.+\.edu.

- The plus sign,

- Languages like Python and JavaScript support regular expressions, which are like a mini-language in themselves, with syntax like:

.for any character.*for 0 or more characters.+for 1 or more characters?for an optional character^for start of input$for end of input- …

- We can change our program earlier to use

re, a Python library for regular expressions:import csv import re counter = 0 with open("favorites.csv", "r") as file: reader = csv.DictReader(file) for row in reader: title = row["title"].strip().upper() if re.search("OFFICE", title): counter += 1 print(f"Number of people who like The Office: {counter}")$ python favorites.py Number of people who like The Office: 16- The

relibrary has a function,search, to which we can pass a pattern and string to see if there is a match. - We can change our expression to

"^(OFFICE|THE OFFICE)$", which will match eitherOFFICEorTHE OFFICE, but only if they start at the beginning of the string, and stop at the end of the string (i.e., there are no other words before or after). - We can even change

THE OFFICEtoTHE.OFFICE, allowing any character (like a typo) to be in between those words.

- The

- We can also write a program to ask the user for a particular title and report its popularity:

import csv title = input("Title: ").strip().upper() counter = 0 with open("favorites.csv", "r") as file: reader = csv.DictReader(file) for row in reader: if row["title"].strip().upper() == title: counter += 1 print(counter)$ python favorites.py Title: the office 13- We ask the user for input, and then open our CSV file. Since we’re looking for just one title, we can have one

countervariable that we increment. - We check for a match after standardizing both the user’s input and each row’s title.

- We ask the user for input, and then open our CSV file. Since we’re looking for just one title, we can have one

Relational databases

- Relational databases are programs that store data, ultimately in files, but with additional data structures and interfaces that allow us to search and store data more efficiently.

- When working with data, we generally need four types of basic operations with the acronym

CRUD:CREATEREADUPDATEDELETE

SQL

- With another programming language, SQL (pronounced like “sequel”), we can interact with databases with verbs like:

CREATE,INSERTSELECTUPDATEDELETE,DROP

- Syntax in SQL might look like:

CREATE TABLE table (column type, ...);- With this statement, we can create a table, which is like a spreadsheet with rows and columns.

- In SQL, we choose the types of data that each column will store.

- We’ll use a common database program called SQLite, one of many available programs that support SQL. Other database programs include Oracle Database, MySQL, PostgreSQL, and Microsoft Access.

- SQLite stores our data in a binary file, with 0s and 1s that represent data efficiently. We’ll interact with our tables of data through a command-line program,

sqlite3. - We’ll run some commands in VS Code to import our CSV file into a database:

$ sqlite3 favorites.db SQLite version 3.36.0 2021-06-18 18:36:39 Enter ".help" for usage hints. sqlite> .mode csv sqlite> .import favorites.csv favorites- First, we’ll run the

sqlite3program withfavorites.dbas the name of the file for our database. - With

.import, SQLite creates a table in our database with the data from our CSV file.

- First, we’ll run the

- Now, we’ll see three files, including

favorites.db:$ ls favorites.csv favorites.db favorites.py - We can open our database file again, and check the schema, or design, of our new table with

.schema:$ sqlite3 favorites.db SQLite version 3.36.0 2021-06-18 18:36:39 Enter ".help" for usage hints. sqlite> .schema CREATE TABLE IF NOT EXISTS "favorites"( "Timestamp" TEXT, "title" TEXT, "genres" TEXT );- We see that

.importused theCREATE TABLE ...command to create a table calledfavorites, with column names automatically copied from the CSV’s header row, and types for each of them assumed to be text.

- We see that

- We can select, or read data, with:

sqlite> SELECT title FROM favorites; +------------------------------------+ | title | +------------------------------------+ | How i met your mother | | The Sopranos | | Friday Night Lights | ...- With a command in the format

SELECT columns FROM table;, we can read data from one or more columns. For example, we can writeSELECT title, genre FROM favorites;to select both the title and genre.

- With a command in the format

- SQL supports many functions that we can use to count and summarize data:

AVGCOUNTDISTINCTLOWERMAXMINUPPER- …

- We can clean up our titles as before, converting them to uppercase and printing only the unique values:

sqlite> SELECT DISTINCT(UPPER(title)) FROM shows; ... | LAW AND ORDER | | B99 | | GOT | ... - We can also get a count of how many responses there are:

sqlite> SELECT COUNT(title) FROM favorites; +--------------+ | COUNT(title) | +--------------+ | 158 | +--------------+ - We can also add more phrases to our command:

WHERE, adding a Boolean expression to filter our dataLIKE, filtering responses more looselyORDER BYLIMITGROUP BY- …

- We can limit the number of results:

sqlite> SELECT title FROM favorites LIMIT 10; +-----------------------+ | title | +-----------------------+ | How i met your mother | | The Sopranos | | Friday Night Lights | | Family Guy | | New Girl | | Friends | | Office | | Breaking Bad | | Modern Family | | Office | +-----------------------+ - We can also look for titles matching a string:

sqlite> SELECT title FROM favorites WHERE title LIKE "%office%"; +-------------+ | title | +-------------+ | Office | | Office | | The Office | | The Office | | The Office | | The Office | | The Office | | The Office | | The Office | | The Office | | The Office | | the office | | The Office | | ThE OffiCE | | The Office | | Thevoffice | +-------------+- The

%character is a placeholder for zero or more other characters, so SQL supports some pattern matching, though not it’s not as powerful as regular expressions are.

- The

- We can select just the count in our command:

sqlite> SELECT COUNT(title) FROM favorites WHERE title LIKE "%office%"; +--------------+ | COUNT(title) | +--------------+ | 16 | +--------------+ - If we don’t like a show, we can even delete it:

sqlite> SELECT COUNT(title) FROM favorites WHERE title LIKE "%friends%"; +--------------+ | COUNT(title) | +--------------+ | 9 | +--------------+ sqlite> DELETE FROM favorites WHERE title LIKE "%friends%"; sqlite> SELECT COUNT(title) FROM favorites WHERE title LIKE "%friends%"; +--------------+ | COUNT(title) | +--------------+ | 0 | +--------------+- With SQL, we can change our data more easily and quickly than with Python.

- We can update a specific row of data:

sqlite> SELECT title FROM favorites WHERE title = "Thevoffice"; +------------+ | title | +------------+ | Thevoffice | +------------+ sqlite> UPDATE favorites SET title = "The Office" WHERE title = "Thevoffice"; sqlite> SELECT title FROM favorites WHERE title = "Thevoffice"; sqlite>- Now, we’ve changed that row’s value.

- We can change the values in multiple rows, too:

sqlite> SELECT genres FROM favorites WHERE title = "Game of Thrones"; +--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------+ | genres | +--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------+ | Action, Adventure, Drama, Fantasy, Thriller, War | | Action, Adventure, Drama | | Action, Adventure, Comedy, Drama, Family, Fantasy, History, Horror, Musical, Mystery, Romance, Thriller, War | | Action, Drama, Family, Fantasy, War | | Fantasy, Thriller, War | +--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------+ sqlite> UPDATE favorites SET genres = "Action, Adventure, Drama, Fantasy, Thriller, War" WHERE title = "Game of Thrones"; sqlite> SELECT genres FROM favorites WHERE title = "Game of Thrones"; +--------------------------------------------------+ | genres | +--------------------------------------------------+ | Action, Adventure, Drama, Fantasy, Thriller, War | | Action, Adventure, Drama, Fantasy, Thriller, War | | Action, Adventure, Drama, Fantasy, Thriller, War | | Action, Adventure, Drama, Fantasy, Thriller, War | | Action, Adventure, Drama, Fantasy, Thriller, War | +--------------------------------------------------+ - With

DELETEandDROP, we can remove rows and even entire tables as well. - And notice that in our commands, we’ve written SQL keywords in all caps, so they stand out more.

- There also isn’t a built-in way to undo commands, so if we make a mistake we might have to build our database again!

Tables

- We’ll take a look at our schema again:

sqlite> .schema CREATE TABLE IF NOT EXISTS "favorites"( "Timestamp" TEXT, "title" TEXT, "genres" TEXT ); - If we look at our values of genres, we see some redundancy:

sqlite> SELECT genres FROM favorites; +-----------------------------------------------------------+ | genres | +-----------------------------------------------------------+ | Comedy | | Comedy, Crime, Drama, Horror, Sci-Fi, Talk-Show, Thriller | | Drama, Family, Sport | | Animation, Comedy | | Comedy, Drama | ... - And if we want to search for shows that are comedies, we have to search with not just

SELECT title FROM favorites WHERE genre = "Comedy";, but also... WHERE genre = "Comedy, Drama";,... WHERE genre = "Comedy, News";, and so on. - We can use the

LIKEkeyword again, but two genres, “Music” and “Musical”, are similar enough for that to be problematic. - We can actually write our own Python program that will use SQL to import our CSV data into two tables:

# Imports titles and genres from CSV into a SQLite database import cs50 import csv # Create database open("favorites8.db", "w").close() db = cs50.SQL("sqlite:///favorites8.db") # Create tables db.execute("CREATE TABLE shows (id INTEGER, title TEXT NOT NULL, PRIMARY KEY(id))") db.execute("CREATE TABLE genres (show_id INTEGER, genre TEXT NOT NULL, FOREIGN KEY(show_id) REFERENCES shows(id))") # Open CSV file with open("favorites.csv", "r") as file: # Create DictReader reader = csv.DictReader(file) # Iterate over CSV file for row in reader: # Canoncalize title title = row["title"].strip().upper() # Insert title show_id = db.execute("INSERT INTO shows (title) VALUES(?)", title) # Insert genres for genre in row["genres"].split(", "): db.execute("INSERT INTO genres (show_id, genre) VALUES(?, ?)", show_id, genre)- First, we import the Python

cs50library so we can run SQL commands more easily. - Then, the rest of this code will import each row of

favorites.csv.

- First, we import the Python

- Now, our database will have this design:

$ sqlite3 favorites8.db SQLite version 3.36.0 2021-06-18 18:36:39 Enter ".help" for usage hints. sqlite> .schema CREATE TABLE shows (id INTEGER, title TEXT NOT NULL, PRIMARY KEY(id)); CREATE TABLE genres (show_id INTEGER, genre TEXT NOT NULL, FOREIGN KEY(show_id) REFERENCES shows(id));- We have one table,

shows, with anidcolumn and atitlecolumn. We can specify that atitleisn’t null, and thatidis the column we want to use as a primary key. - Then, we’ll have a table called

genres, where we have ashow_idcolumn that references ourshowstable, along with agenrecolumn. - This is an example of a relation, like a link, between rows in different tables in our database.

- We have one table,

- In our

showstable, we’ll see each show with anidnumber:sqlite> SELECT * FROM shows; +-----+------------------------------------+ | id | title | +-----+------------------------------------+ | 1 | HOW I MET YOUR MOTHER | | 2 | THE SOPRANOS | | 3 | FRIDAY NIGHT LIGHTS | | 4 | FAMILY GUY | | 5 | NEW GIRL | | 6 | FRIENDS | | 7 | OFFICE | ... - And we can see that the

genrestable has one or more rows for eachshow_id:sqlite> SELECT * FROM genres; +---------+-------------+ | show_id | genre | +---------+-------------+ | 1 | Comedy | | 2 | Comedy | | 2 | Crime | | 2 | Drama | | 2 | Horror | | 2 | Sci-Fi | | 2 | Talk-Show | | 2 | Thriller | | 3 | Drama | | 3 | Family | | 3 | Sport | | 4 | Animation | | 4 | Comedy | | 5 | Comedy | | 6 | Comedy | | 7 | Comedy | ...- Since each show may have more than one genre, we can have more than one row per show in our

genrestable, known as a one-to-many relationship. - Furthermore, the data is now cleaner, since each genre name is in its own row.

- Since each show may have more than one genre, we can have more than one row per show in our

- We can select all the shows are that comedies by selecting from the

genrestable first, and then looking for thoseids in theshowstable:sqlite> SELECT title FROM shows WHERE id IN (SELECT show_id FROM genres WHERE genre = "Comedy"); +------------------------------------+ | title | +------------------------------------+ | HOW I MET YOUR MOTHER | | THE SOPRANOS | | FAMILY GUY | | NEW GIRL | | FRIENDS | | OFFICE | | MODERN FAMILY | ...- Notice that we’ve nested two queries, where the inner one returns a list of show

ids, and the outer one uses those to select the titles of shows that match.

- Notice that we’ve nested two queries, where the inner one returns a list of show

- Now we can sort and show just the unique titles by adding to our command:

sqlite> SELECT DISTINCT(title) FROM shows WHERE id IN (SELECT show_id FROM genres WHERE genre = "Comedy") ORDER BY title; +------------------------------------+ | title | +------------------------------------+ | ARCHER | | ARRESTED DEVELOPMENT | | AVATAR THE LAST AIRBENDER | | B99 | | BILLIONS | | BLACK MIRROR | ... - And we can add new data to each table, in order to add another show. First, we’ll add a new row to the

showstable for Seinfeld:sqlite> INSERT INTO shows (title) VALUES("Seinfeld"); - Then, we can get our row’s

idby looking for it in the table:sqlite> SELECT * FROM shows WHERE title = "Seinfeld"; +-----+----------+ | id | title | +-----+----------+ | 159 | Seinfeld | +-----+----------+ - We’ll use that as the

show_idto add a new row in thegenrestable:sqlite> INSERT INTO genres (show_id, genre) VALUES(159, "Comedy"); - Then, we’ll use

UPDATEto set the title to uppercase:sqlite> UPDATE shows SET title = "SEINFELD" WHERE title = "Seinfeld"; - Finally, we’ll run the same command as before, and see our new show is indeed in the list of comedies:

sqlite> SELECT DISTINCT(title) FROM shows WHERE id IN (SELECT show_id FROM genres WHERE genre = "Comedy") ORDER BY title; ... | SEINFELD | ...

SQL with Python

- It turns out that we’ll be able to write Python code that automates this, so we can imagine building web applications that can programmatically store and look up user data, online shopping orders, and more.

- We can write a program that asks the user for a show title and then prints its popularity:

import csv from cs50 import SQL db = SQL("sqlite:///favorites.db") title = input("Title: ").strip() rows = db.execute("SELECT COUNT(*) AS counter FROM favorites WHERE title LIKE ?", title) row = rows[0] print(row["counter"])- We’ll use the

cs50library to run SQL commands more easily, and open thefavorites.dbdatabase we created earlier. - We’ll prompt the user for a title, and then execute a command. A

?in the command will allow us to safely substitute variables in our command. - The results are returned in a list of rows, and

COUNT(*)returns just one row. In our command, we’ll addAS counter, so the count is returned in the row (which is a dictionary) with the column namecounter.

- We’ll use the

- We can run our program and search for “The Office”:

$ python favorites.py Title: The Office 12 - And we can tweak our program to print all the rows that match:

import csv from cs50 import SQL db = SQL("sqlite:///favorites.db") title = input("Title: ").strip() rows = db.execute("SELECT title FROM favorites WHERE title LIKE ?", title) for row in rows: print(row["title"])$ python favorites.py Title: The Office The Office The Office The Office The Office The Office The Office The Office The Office the office The Office ThE OffiCE The Office The Office- Since

LIKEis case-insensitive, we see all the various ways the titles were capitalized.

- Since

IMDb

- IMDb, or the Internet Movie Database, has datasets available for download as TSV (tab-separated values) files.

- We’ll open a database that the staff has created beforehand:

$ sqlite3 shows.db SQLite version 3.36.0 2021-06-18 18:36:39 Enter ".help" for usage hints. sqlite> .schema CREATE TABLE shows ( id INTEGER, title TEXT NOT NULL, year NUMERIC, episodes INTEGER, PRIMARY KEY(id) ); CREATE TABLE genres ( show_id INTEGER NOT NULL, genre TEXT NOT NULL, FOREIGN KEY(show_id) REFERENCES shows(id) ); CREATE TABLE stars ( show_id INTEGER NOT NULL, person_id INTEGER NOT NULL, FOREIGN KEY(show_id) REFERENCES shows(id), FOREIGN KEY(person_id) REFERENCES people(id) ); CREATE TABLE writers ( show_id INTEGER NOT NULL, person_id INTEGER NOT NULL, FOREIGN KEY(show_id) REFERENCES shows(id), FOREIGN KEY(person_id) REFERENCES people(id) ); CREATE TABLE ratings ( show_id INTEGER NOT NULL, rating REAL NOT NULL, votes INTEGER NOT NULL, FOREIGN KEY(show_id) REFERENCES shows(id) ); CREATE TABLE people ( id INTEGER, name TEXT NOT NULL, birth NUMERIC, PRIMARY KEY(id) );- Notice that we have multiple tables, each of which has columns of various data types.

- In both the

starsandwriterstable, for example, we have ashow_idcolumn that references theidof some row in theshowstable, and aperson_idcolumn that references theidof some row in thepeopletable. Effectively, they link shows and people by theirids.

- It turns out that SQL, too, has its own data types:

BLOB, for “binary large object”, raw binary data that might represent filesINTEGERNUMERIC, number-like but not quite a number, like a date or timeREAL, for floating-point valuesTEXT, like strings

- Columns can also have additional attributes:

PRIMARY KEY, like theidcolumns above that will be used to uniquely identify each rowFOREIGN KEY, like theshow_idcolumn above that refers to a column in some other table

- We can see that there are millions of rows in the

peopletable:sqlite> SELECT * FROM people; ... | 13058200 | Emilio Mancuso | | | 13058201 | Pietro Furnis | | | 13058202 | Ida Lonati Frati | | +----------+-----------------------------------------------------+-------+ - But like before, we can search for just one row:

sqlite> SELECT * FROM people WHERE name = "Steve Carell"; +--------+--------------+-------+ | id | name | birth | +--------+--------------+-------+ | 136797 | Steve Carell | 1962 | +--------+--------------+-------+ - It turns out that there are a few shows titled “The Office”:

sqlite> SELECT * FROM shows WHERE title = "The Office"; +---------+------------+------+----------+ | id | title | year | episodes | +---------+------------+------+----------+ | 112108 | The Office | 1995 | 6 | | 290978 | The Office | 2001 | 14 | | 386676 | The Office | 2005 | 188 | | 1791001 | The Office | 2010 | 30 | | 2186395 | The Office | 2012 | 8 | | 8305218 | The Office | 2019 | 28 | +---------+------------+------+----------+ - The most popular one, with 188 episodes, is the one we want, so we can get just that one:

sqlite> SELECT * FROM shows WHERE title = "The Office" and year = "2005"; +--------+------------+------+----------+ | id | title | year | episodes | +--------+------------+------+----------+ | 386676 | The Office | 2005 | 188 | +--------+------------+------+----------+ - We can turn on a timer and see that our original command took about 0.02 seconds to run:

sqlite> .timer on sqlite> SELECT * FROM shows WHERE title = "The Office"; +---------+------------+------+----------+ | id | title | year | episodes | +---------+------------+------+----------+ | 112108 | The Office | 1995 | 6 | | 290978 | The Office | 2001 | 14 | | 386676 | The Office | 2005 | 188 | | 1791001 | The Office | 2010 | 30 | | 2186395 | The Office | 2012 | 8 | | 8305218 | The Office | 2019 | 28 | +---------+------------+------+----------+ Run Time: real 0.021 user 0.016419 sys 0.004117 - We can create an index, or additional data structures that our database program will use for future searches:

sqlite> CREATE INDEX "title_index" ON "shows" ("title"); Run Time: real 0.349 user 0.195206 sys 0.051217 - Now, our search command takes nearly no time:

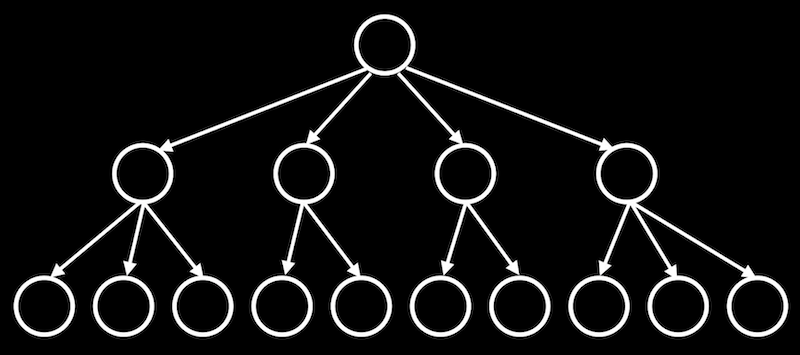

sqlite> SELECT * FROM shows WHERE title = "The Office"; +---------+------------+------+----------+ | id | title | year | episodes | +---------+------------+------+----------+ | 112108 | The Office | 1995 | 6 | | 290978 | The Office | 2001 | 14 | | 386676 | The Office | 2005 | 188 | | 1791001 | The Office | 2010 | 30 | | 2186395 | The Office | 2012 | 8 | | 8305218 | The Office | 2019 | 28 | +---------+------------+------+----------+ Run Time: real 0.000 user 0.000104 sys 0.000124 - It turns out that these data structures are generally B-trees, like binary trees we’ve seen in C but with more children, with nodes organized such that we can search faster than linearly:

- Creating an index takes some time up front, perhaps by sorting the data, but afterwards we can search much more quickly.

- With our data spread among different tables, we can nest our queries to get useful data. For example, we can get all the titles of shows starring a particular person:

sqlite3> SELECT title FROM shows WHERE id IN (SELECT show_id FROM stars WHERE person_id = (SELECT id FROM people WHERE name = "Steve Carell")); +------------------------------------+ | title | +------------------------------------+ | The Dana Carvey Show | | Over the Top | | Watching Ellie | | Come to Papa | | The Office | ...- We’ll

SELECTthetitlefrom theshowstable for shows with anidthat matches a list ofshow_ids from thestarstable. Thoseshow_ids, in turn, must have aperson_idthat matches theidof Steve Carell in thepeopletable.

- We’ll

- Our query runs pretty quickly, but we can create a few more indexes:

sqlite> CREATE INDEX person_index ON stars (person_id); Run Time: real 0.890 user 0.662294 sys 0.097505 sqlite> CREATE INDEX show_index ON stars (show_id); Run Time: real 0.644 user 0.469162 sys 0.058866 sqlite> CREATE INDEX name_index ON people (name); Run Time: real 0.840 user 0.609600 sys 0.088177- Each index takes almost a second to build, but afterwards, our same query takes very little time to run.

- It turns out that we can use

JOINcommands to combine tables in our queries:sqlite> SELECT title FROM people ...> JOIN stars ON people.id = stars.person_id ...> JOIN shows ON stars.show_id = shows.id ...> WHERE name = "Steve Carell";- With the

JOINsyntax, we can virtually combine tables based on their foreign keys, and use their columns as though they were one table. Here, we’re matching thepeopletable with thestarstable, and then with theshowstable.

- With the

- We can format the same query a little better by listing the tables we want to use all at once:

sqlite> SELECT title FROM people, stars, shows ...> WHERE people.id = stars.person_id ...> AND stars.show_id = shows.id ...> AND name = "Steve Carell"; +------------------------------------+ | title | +------------------------------------+ | The Dana Carvey Show | | Over the Top | | Watching Ellie | | Come to Papa | | The Office | - The downside to having lots of indexes is that each of them take up some amount of space, which might become significant with lots of data and lots of indexes.

Problems

- One problem in SQL is called a SQL injection attack, where an someone can inject, or place, their own commands into inputs that we then run on our database.

- We might encounter a login page for a website that asks for a username and password, and checks for those in a SQL database.

- Our query for searching for a user might be:

rows = db.execute("SELECT * FROM users WHERE username = ? AND password = ?", username, password) if len(rows) == 1: # Log user in- By using the

?symbols as placeholders, our SQL library will escape the input, or prevent dangerous characters from being interpreted as part of the command.

- By using the

- In contrast, we might have a SQL query that’s a formatted string, such as:

rows = db.execute(f"SELECT * FROM users WHERE username = '{username}' AND password = '{password}'") if len(rows) == 1: # Log user in - If a user types in

malan@harvard.edu'--as their input, then the query will end up being:rows = db.execute(f"SELECT * FROM users WHERE username = 'malan@harvard.edu'--' AND password = '{password}'")- This query will actually select the row where

username = 'malan@harvard.edu', without checking the password, since the single quotes end the input, and--turns the rest of the line into a comment in SQL.

- This query will actually select the row where

- The user could even add a semicolon,

;, and write a new command of their own, that our database will execute. - Another set of problems with databases are race conditions, where shared data is unintentionally changed by code running on different devices or servers at the same time.

- One example is a popular post getting lots of likes. A server might try to increment the number of likes, asking the database for the current number of likes, adding one, and updating the value in the database:

rows = db.execute("SELECT likes FROM posts WHERE id = ?", id); likes = rows[0]["likes"] db.execute("UPDATE posts SET likes = ? WHERE id = ?", likes + 1, id);- Two different servers, responding to two different users, might get the same starting number of likes since the first line of code runs at the same time on each server.

- Then, both will use

UPDATEto set the same new number of likes, even though there should have been two separate increments.

- Another example might be of two roommates and a shared fridge in their dorm. The first roommate comes home, and sees that there is no milk in the fridge. So the first roommate leaves to the store to buy milk. While they are at the store, the second roommate comes home, sees that there is no milk, and leaves for another store to get milk as well. Later, there will be two jugs of milk in the fridge.

- We can solve this problem by locking the fridge so that our roommate can’t check whether there is milk until we’ve gotten back.

- To solve this problem, SQL supports transactions, where we can lock rows in a database, such that a particular set of actions are atomic, or guaranteed to happen together.

- For example, we can fix our problem above with:

db.execute("BEGIN TRANSACTION") rows = db.execute("SELECT likes FROM posts WHERE id = ?", id); likes = rows[0]["likes"] db.execute("UPDATE posts SET likes = ? WHERE id = ?", likes + 1, id); db.execute("COMMIT")- The database will ensure that all the queries in between are executed together.

- But the more transactions we have, the slower our applications might be, since each server has to wait for other servers’ transactions to finish.